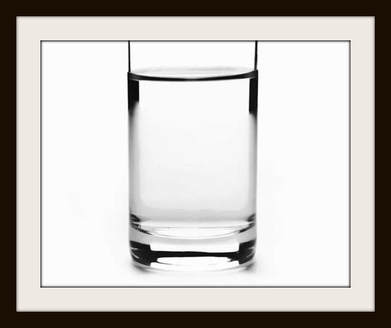

Does the Current Frame Always Matter Most?Intuitively, we know that there are different ways of thinking about things: The same proverbial glass can be seen as half full or half empty. Indeed, research across multiple disciplines has shown that people's evaluations depend on how something is framed, or described: People like the proverbial glass when it’s described as half full, and they dislike it when it’s described as half empty. Similarly, people like a politician when her record is framed in terms of successes more than when that same record is framed in terms of failures. But what happens when the description changes? Can people switch back and forth from one conceptualization to another, or do they get stuck in one way of thinking?

|

Negative Frames Stick in the Mind

Integrating work on functional fixedness, framing, and negativity bias, we hypothesized that negative frames might be fundamentally “stickier” than positive frames, so that it is more difficult for people to shift from conceptualizing an issue in terms of negatives to reconceptualizing it in terms of positives (compared to shifting from positives to negatives). In an NSF-funded project, we borrowed classic paradigms in framing research (such as Tversky and Kahneman’s “unusual disease” scenario) and added a twist: After participants saw information framed in terms of either negatives (e.g., lives lost) or positives (e.g., lives saved), they saw the same information reframed in the opposite way. Consistent with the notion that negative frames are conceptually stickier than positive frames, negative-to-positive reframing had a muted impact on participants’ risk preferences and evaluations, compared to positive-to-negative reframing. In other experiments, participants took longer to solve a simple math problem that required reconceptualizing negatives as positives, compared to when the same math problem involved mentally converting from positives to negatives.

Are Positives Ever Sticky?

Recent research in our lab suggests that positive frames can stick too, when people are contemplating something unfamiliar and potentially rewarding. This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective: Humans can't always think about potential negatives more than potential positives, or else they would just cower in the corner, afraid to ever go out and explore a new environment in search of potential rewards. In new or unfamiliar territory, when rewards are not yet learned, there might instead be a positivity bias to help push people toward exploration. Our research in this area draws from theorizing on regulatory focus and positivity offset to pull apart two concepts that have all too often been conflated in the interdisciplinary literature on framing: Gains (rewards) versus losses (punishments), and positive frames (the possibility of getting a reward OR avoiding a punishment) versus negative frames (the possibility of missing a reward OR receiving a punishment). Our theoretical framework offers new predictions about when positive and negative frames will stick in the mind and resist reframing, and can be fruitfully applied to many other domains.

Does Everyone Show The Same Biases?

Research on so-called "basic" psychological biases often assumes that these they reflect general human tendencies that characterize everyone equally. Yet there are theoretical reasons to expect that not everyone will show the negativity bias in reframing effects described above. Recent research in our lab combined data from all of our previous studies on reframing in the loss domain to test the potential moderating role of age. The results suggest that the negativity bias in reframing effects diminishes across the lifespan, and may disappear entirely around age 60. In another project, we are collaborating with researchers at the University of Sharjah to examine reframing effects across cultures.

How Can You Get Unstuck from Negative Frames?

Current research in our lab examines what makes an initial frame more or less sticky. For example, in a recent project led by former undergraduate student Melisse Liwag and former PhD student Dr. Andre Wang, we explored whether giving a policy a new name might release people from the effects of a previously encountered negative frame.